Martina Ricci

I visit Bosnia and Herzegovina nearly every year to gather credible sources in support of my PhD thesis. I do this with the intention of collecting material that will serve to validate the argumentation underlying my research. It’s exhausting work, but one that persistence has accustomed me to during the last three years. Therefore, this was not my first visit to Bosnia. This time the journey coincided with a deeply painful week for Bosniak, the term by which Bosnians of the Muslim faith are identified. The week of the commemoration of the genocide of more than 8,000 men and boys, systematically slaughtered by Mladić’s troops in July 1995 in a vile and cruel ethnic cleansing operation.

I had already taken part in the official commemorations of the genocide, and I had done so two years earlier, right at the Memorial Centre in Potočari, a place of burial, mourning, and memory. I had arrived in the Bosnian village in an unusual manner, after unexpected stops, delays, and detours. I remember noticing crowds of people gathered under the shade of a few evergreen trees and people eating beside gravestones, perhaps attempts to reconstruct ordinary habits, despite having lost those with whom such rituals were once shared. But what stayed with me most of all was the awareness that in that place, death was a shared fate. A family’s mourning was not a unique event compared to others’ experiences. Death was everywhere, woven into the community’s sorrow and historical trauma, into everyone’s helplessness and solitude. The pain was deeply unsettling, and it was for all who were present, precisely because it was a shared pain, suffering that manages to insinuate itself into the hearts of those who haven’t lived it personally. In the desperation of the mother weeping over her son’s mortal remains, in the testimony of remorse, in the memory of a life cut short without mercy, I allowed all the emotion and helplessness I had known to resonate within me. We are all destined to endure suffering, but some forms of pain are so enormous that consciousness can only freeze and crystallize in a state of disbelief.

This year, precisely on July 11th, 2025, the 30th anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide was commemorated. I meditated at length on whether to return to those places and pay homage with my presence to the victims and their families. I told myself I would rather honor the memory of lives broken so prematurely in a different way. I chose to remain in the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina since Sarajevo’s atmosphere still carries the weight of the events. Staying there meant that I could engage with this echo in a way that was both intellectually and personally meaningful: close enough to sense how the traces of the past still shape the city and its people, but also distant enough to maintain the critical perspective I needed. Therefore, I remained in the capital city, far enough from the geographical center of memory but still close enough to feel it.

In Sarajevo, however, the genocide is a specter that insinuates itself relentlessly and unstoppably, penetrating brutally into daily life. It erupts silently, manifesting itself with the white flower with eleven petals, a symbol created for commemorative purposes, making space on walls, pinned to passersby’s jackets, in public gardens, even covering street signs. I noticed them on public buses too, but not on the side panels, not even in the spaces usually destined for advertising. They were placed where the LEDs indicate the destination of the vehicles, in a silent confrontation between the route to be taken and the collective commitment of memory. Pain should be stared at, not oust away in the drawer of things too big to handle. That little white flower was insisting on blooming exactly where you’d rather not see it: on streets, on roundabouts, on bus, even in public buildings, like theatres. Since June 27, 2025, the screenplay Flowers of Srebrenica has taken the stage at the Sarajevo War Theatre by employing personal testimonies to narrate the genocide and its aftermath, not to console, but to ask for remembrance.

And then there are the murals and street art, corollaries of warnings not to forget what happened in July 1995. Walking on Maršala Tita Ulica, at the intersection with Alija Ishakovic Ulica, what welcomes the passerby is an imposing mural on the wall of a building still battered by mortar strikes: Remembering Srebrenica, accompanied by the flower with white petals, giant and majestic. And while war-scarred Sarajevo sometimes seems to look back to the happier days of the ’84 Winter Olympics, through omnipresent stickers, slogans and graffiti of Vučko the wolf, the event’s mascot, this juxtaposition creates a visual competition in the public space, where memories of a festive past collide with more urgent, political, and painful messages. In fact, graffiti bearing the number 8372, the official death toll, are a frequent sight, alongside slogans colored in green and white: Srebrenica, Srebrenica 1995, Never Forget. These appear throughout the city, especially in the Ferhadija area.

Human solidarity is also expressed toward victims of more recent massacres, often juxtaposed with the Bosnian one. The commitment of memory is also a story of interethnic, intergenerational, and international legacy, born from understanding, first and foremost, the universality of suffering and the necessity of justice. “Jučer Srebrenica, danas Gaza, sutra?” (Yesterday Srebrenica, today Gaza, tomorrow?) read the flyers posted everywhere in Baščaršija. Since 2023, these annual calls to action have drawn a direct parallel between the genocide of Srebrenica and what is described as an ongoing genocide in Gaza, invoking the memory of one to call attention to the other. These appeals extend the relevance of the past into the present, shaping a sense of justice, belonging, and responsibility that connects Sarajevo’s local memory to broader global struggles.

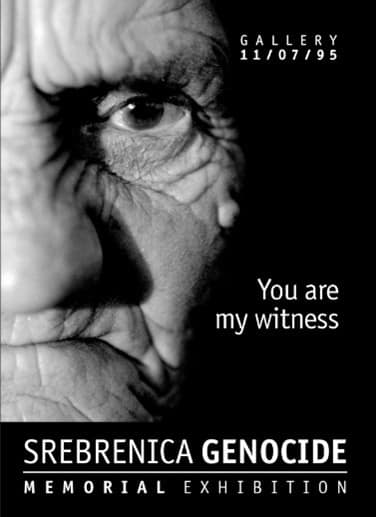

In Sarajevo there are many warnings displayed to guard against possible future horrors, while remembering others. Above the monument of Vječna Vatra, dedicated to the martyrs of World War II, the face of an anguished and desperate elderly mother has appeared. Her suffering, displayed in a massive photograph, promotes the exhibition Underground – Beneath the Earth, inaugurated last July 10th at the Vijećnica, the Sarajevo’s City Hall, which contains authentic photographs of mortal remains taken in mass graves near Srebrenica.

It’s always the face of an elderly woman, this time stiffened by pain, but proud and upright, towering a few meters ahead, beside the majestic Cathedral, in the city center. Again, a face sits in the window for the benefit of passersby, still a face that draws the gaze of others, always a face that invites access to that permanent exhibition at Gallery 11/07/95 of which the lady in the foreground must be more spokesperson than witness. The exhibition exists to tell the story of Srebrenica as both a tragedy and a warning, an echo, a stage for mourning dressed as an installation with authentic photographs and original testimonies.

In Sarajevo, the memory of Srebrenica is an integral part of the visual tapestry of the city, and such pervasiveness isn’t confined to one day a year, but manifests in a latent, daily, even domestic form. And it’s not only the expression of an ethical need to remember, or a political request for recognition: it’s a memory that has identity status, evident through spontaneous initiatives as well as institutional or structured projects, whether public or private. Srebrenica, in Sarajevo, is not just the memory of the ultimate tragedy, but an architectural element. It is not only evoked, it is lived and is present in all its heaviness. It is as if part of urban physiognomy was built precisely to contain, expand, and circulate the testimony of that massacre as well, beyond its own experience as a besieged city. Srebrenica permeates and saturates Sarajevo, reconfiguring its emotional geography. It’s a permanent cry, embodied by the statue of Ramo Osmanović, desperately calling out to his son Nermin, both real people, later found in mass graves near Srebrenica. Nermine, dođi (Nermin, come), this small spomenik in the heart of Veliki Park, just steps away from the well-known Memorial to the Children Killed During the Siege, stands as a call to reminder, urging the preservation of memory despite the fragile ground of denialism.

Far from the site where the massacre occurred, yet still within a profoundly marked landscape, the memory of the genocide continues to circulate. Beyond official and local commemorations, it appears in daily manifestations, filtering through the mechanisms of popular and visual cultures, insidiously spreading in the urban fabric, infused with the intentions we weave into it, whether to remember, to interpret or to call for action. It’s a memory that persists among those who remain. But, at the same time, many have long sought to move forward, to rebuild and imagine futures beyond war, even as the traces of the past remain omnipresent, sometimes as a burden, sometimes as a resource, often as a commodity within the logic of dark tourism.

The images of Srebrenica and its symbols, dates and slogans, are so central in urban geography that they become objects of appropriation not only by victims’ families or activists, but also by anyone who sets foot in this city: tourists, the curious, cultural practitioners, even merchants. They wear T-shirts, collect symbols, and proudly pin the white-petaled flower. At first glance, these gestures can resemble tourist practices, a kind of consumer-friendly memorabilia that risk turning remembrance into ritualized repetitions. I must confess that I have sometimes perceived them in this way: as curated yet fragile attempts at solidarity that may not withstand the weight of the past they claim to honor.

And yet, the more I reflect on it, the less I feel entitled to dismiss these practices. Who am I, as a researcher and as an outsider, to determine what counts as authentic memory work? For some, wearing a flower may be the only accessible way to signal belonging, to express solidarity, or to initiate a conversation with others. Perhaps a badge functions as a portable reminder, carrying memory into spaces where official commemorations do not reach. And, I must admit, I too keep carrying the flower badge with me in my bag, as if it had silently become part of my own baggage of memory.

At the same time, it is undeniable that Sarajevo and Bosnia more broadly have integrated the memory of war and genocide into their cultural economy. Dark tourism, along with objects and souvenirs that have become ubiquitous across the urban landscape, constitutes an important element of how the city sustains itself. Commodification is not the opposite of memory, but one of its many vehicles. What matters is not whether these objects exist, but how they are used, how they resonate with people, both locals and tourists, and whether they encourage collective reflection rather than dissipating in an empty ritual.

In the end, I find myself returning to a simple conviction: it is not the act of remembering, nor the material form it takes, that matters most, but the way we engage with it. A flower pinned to a jacket can remain an echoing specter of remembrance, or it can embody a conscious, living gesture of justice and solidarity. The difference lies not in the object, but in the intentions and practices that surround it.

Leave a Reply